By Kamrul Hassan, Communications Officer, UNCDF, Bangladesh and

Md. Forhad Uddin, Chief of Programme, Dnet

Anjuman is 32 years old. She is the owner of a small shop in the Tangail district, just outside of Dhaka. She started her business three years ago with a microfinance loan of 50,000 taka (approx. US$ 600). “At the beginning, people used to say it is odd for a married woman to start a business. Everyone thought I would fail. But I persisted,” Anjuman recalls.

Anjuman does not maintain daily account records, but she keeps a credit book for her debtors. She collects her daily earnings in cash in a wooden box. Her approximate monthly profit is 10,000 taka (approx. US$ 120). Anjuman is proud that she doesn’t need to depend on anyone to support her children. All the nay-sayers now look up to her for business advice.

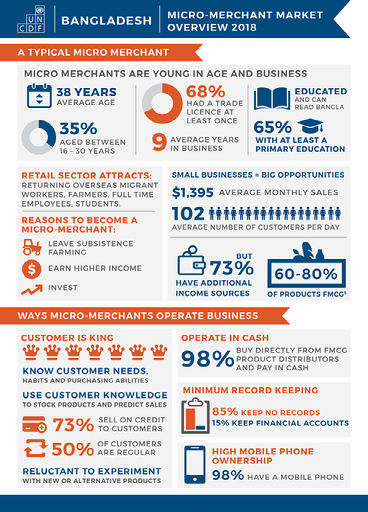

Anjuman is one of 1.3 million micro-merchants working in the Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) retail sector in Bangladesh. Retail micro-merchants represent an enormous market force, with a total market size in annual sales turnover of US$ 18.42 billion, according to UNCDF estimates. The retail sector as a whole represents 13 percent of the country’s GDP. Small and seemingly insignificant on an individual level, micro-merchants as a group account for a substantial part of Bangladesh’s economy, and provide an important source of employment and income for millions. To learn more about retail micro-merchants, see the UNCDF InfoSheet.

Poor micro-merchants face steep barriers, but want to grow

This blog post highlights new findings of qualitative behaviour research with micro-merchants in four of the poorest districts in Bangladesh (Jamalpur, Sirajgonj, Sherpur and Tangail). The research was carried out by Dnet as part of the SHIFT SAARC project “Merchants Development Driving Rural Markets” and complements the landscape assessment’s district breakdown. The research focused on financial behaviours, capacity development needs and uses of information technology.

1) Financial behaviours

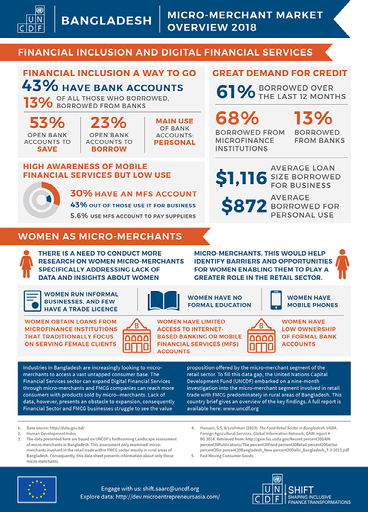

Retail micro-merchants mostly rely on informal sources of finance. They cite access to credit as the main barrier impeding business growth. Digital financial services – if used at all – are limited to non-business related activities.

Most micro-merchants do not own a bank account. Reasons cited include lack of knowledge, complicated and time-consuming account opening procedures, conflicting religious norms and beliefs and lack of funds. Instead, micro-merchants depend on their immediate families, friends and local cooperatives for financial support.

Nearly all micro-merchants point to insufficient access to finance as the main bottleneck to business growth, hindering aspirations such as larger inventories and product diversification. Cash is cited as the preferred method for payments and savings. Though roughly one in three micro-merchants interviewed own mobile money accounts, only a few use them for business-related activities such as paying suppliers. Notably, none of the merchants owns a dedicated merchant account.

2) Capacity development needs

Micro-merchants typically learn from observing their peers. Most are eager to expand their skills, and show particular interest in developing their financial capabilities.

Formal education levels of vary between 10 years of schooling and no formal education at all. A large segment is illiterate, or have low levels of literacy. Nearly all of their industry knowledge, customer understanding and business management skills come from observing and learning from their peers.

Micro-merchants are generally interested in new learning opportunities, particularly in the areas of building and managing savings, cash flow and inventory management, and basic accounting. In terms of adopting innovative technologies, micro-merchants are interested if the solutions are cheap, easy to use and beneficial to their business activities. Interestingly, some are only willing to adopt if their peers are doing so as well.

3) Uses of communication channels

Preferred communication and information channels vary across age, income and education levels. Mobile phone penetration is nearly universal.

Respondents name television, newspapers and mobile voice as their preferred information technologies. Variations are seen depending on age, education levels and access to internet. Nearly all micro-merchants own a mobile phone; younger and more educated individuals are more likely to own a smartphone.

There is no “one size fits all” solution

These key findings suggest that there is no “one size fits all” solution to increasing the growth and competitiveness of the retail micro-merchant sector engaged in FMCG. Rather, we must recognize the diversity and distinctive wants and needs of this vast market segment.

In terms of financial behaviours, the research sheds light on the power of “peer effects”. Whether in the context of access to finance, learning new skills or the willingness to adapt innovative technologies, micro-merchants all emphasized the importance of their peer networks. As some stated, personal relationships are more important than generating profit. Interventions could leverage these interpersonal relationships by appointing “change agents” – community leaders who help educate their peers about new approaches or solutions within retail sector. This is one example that could help drive adoption of new ways of working, particularly in novel areas such as digital financial services.

A practical implication for capacity development is that some micro-merchants need training in basic calculations, while others are ready for more advanced subjects, such as accounting and budgeting. In communications, similarly, information campaigns must account for varying levels of literacy and access to technologies, among other variables among more than a million retail micro-merchants operating across Bangladesh.

More research will identify opportunities for public and private sector

Despite their market size, knowledge and data about this group remains scarce, dampening public and private sector efforts to shape appropriate market interventions. Learning about the business practices, barriers and needs of micro-merchants therefore presents a critical first step to supporting their growth.

In response to this need for knowledge and data, UNCDF with funding from the European Union has partnered with the ICT social enterprise Dnet, the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FBCCI) and the Bangladesh Dokan Malik Samity (BDMS) in implementation of SHIFT SAARC project “Merchants Development Driving Rural Markets”. This blog post is part of the “Micro-merchant research into action (M2A) series” recently launched by UNCDF as part of the project. The series will share data, analysis and insights about retail micro-merchants.